Throughout the artworks in FLESH, skin haunts the edges of paintings, becomes a source of joy and shame, and allows artists to reconsider the idea of the “gaze” throughout art history. Christopher Hartmann suggestively outlines a pile of white socks and Calvin Klein boxers with fleshy peach ripples. Shona McAndrew’s new canvases feature one woman covering her body and another who lounges comfortably on a sunny couch. In Horn of Plenty, Portrait de Laura, Chloë Saï Breil-Dupont dramatically rhymes the light, shadow, and folds of her sitter’s skin with the contours of the lustrous drapery behind her. Lukas Luzius Leichtle focuses on the bottom of his subject’s feet—flesh so rarely seen in art that its appearance on canvas evokes a kind of unsettling intimacy. In his drawings, Guillermo Martín Bermejo employs negative space to conjure the sheen of his own forehead and the slant of his nose. Kurt Kauper’s large-scale composition seems to ask: Is it possible for a male artist to objectively paint a female nude?

Many of these pieces riff on artworks from centuries past. By exhibiting Old Master drawings and prints alongside contemporary work, Newchild Gallery highlights both a continuum and significant ruptures within art history. While the subtle tonalities of flesh have long enchanted artists, ideas about the best way to represent the figure—and which artists can and should depict whom—are always in flux.The works in FLESH chart the ever-evolving relationship between the artist’s hand and the subject’s flesh.

One of the oldest pieces in the exhibition, Rembrandt’s 1656 etching of collector and goldsmith Johannes Lutma, conjures flesh with intricate hatchings. Rembrandt rendered the older artisan with his tools at his side, failing eyes half-opened. The piece suggests a keen interest in blindness—a great theme throughout Rembrandt’s oeuvre—and the artistic process itself. In his Self-portrait (1760) mezzotint, Thomas Frye captured himself at work, “porte-crayon,” or drawing tool, in hand. He depicted his features, from the drooping flesh beneath his eyes to the wispy lines across his forehead, with keen attention to light and shadow and a devotion to portraying the self, and his aging skin, as accurately as possible.

In his own self-portrait, Like Frye, Guillermo Martín Bermejo reinterprets Frye’s work: He also renders himself with his fingertips grazing his own brow, porte-crayon at the ready. In place of Frye’s dark background, Bermejo draws a leafy branch and towers, trees, and mountains that rise in the distance. He meditates on both his own features and on a larger story about creativity and imagination. Another Bermejo drawing features poet Walt Whitman surrounded by young men, whom the artist views as a kind of 19th century “School of Athens.” “My drawings are poems that open a hole in the time,” Bermejo says.

Kurt Kauper and Shona McAndrew reject old models of artist-subject relationships. Instead, they embrace contemporary ideas about power and representation. In his painting, Woman #4 (2017), Kauper has attempted to rethink “the male gaze,” removing any sense of desire or objectification from his slightly-larger-than-life female nude. The result depicts a woman of color who appears nearly supernatural in her strength and forthright posture. The figure floats against a coral-colored background, denying the viewer any additional narrative details.

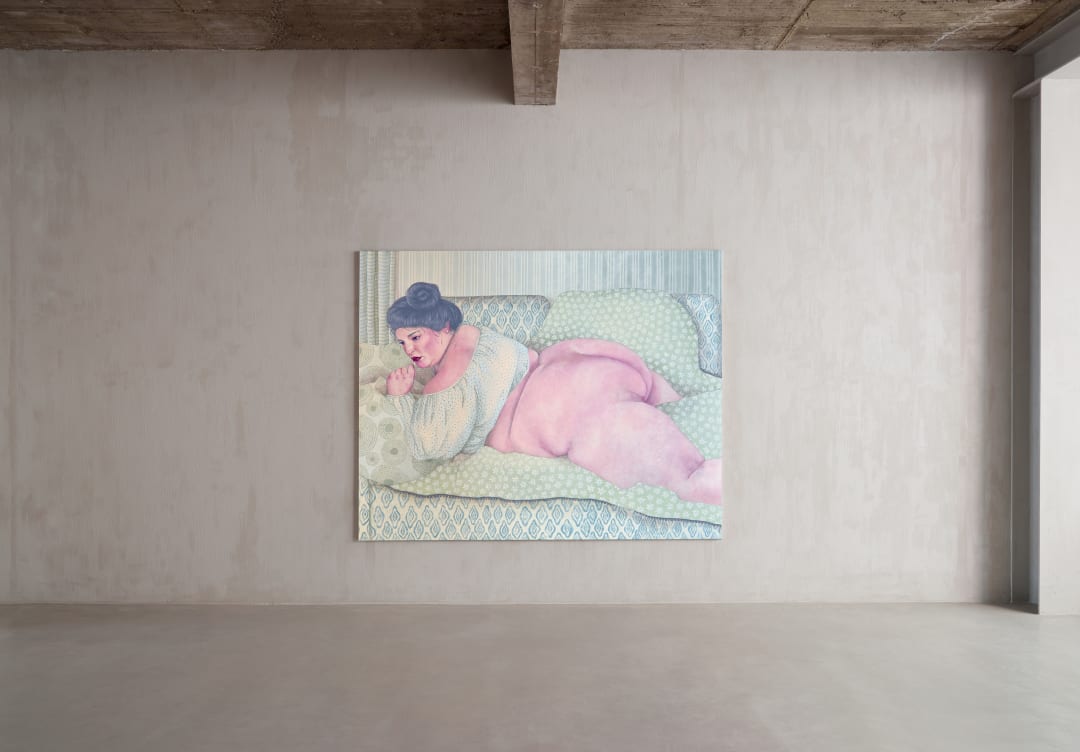

McAndrew, in contrast, wants to tell extensive stories about her subjects, the artistic process, and art history itself. She has created three new paintings for Flesh, reinterpreting odalisques by François Boucher, Francesco Hayez, and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. Throughout her practice, McAndrew has celebrated women—many of them plus-sized, like the artist herself—in vibrant paintings and sculptures that revel in decorative detail. “For this show, I’m back into rejoicing in strong women who love themselves,” she said. She paints her models from photographs, which they take themselves, after McAndrew shares images of the reference paintings with them. This allows for a more collaborative relationship between artist and subject. In her new suite of paintings, McAndrew also renders her subjects’ flesh with more attention, and detail, than ever before. In Enajite, she paints a Black woman lounging on a bright orange couch, holding a cat, with floral wallpaper behind her. “Dark skin isn’t always associated with lightness,” said the artist. “I didn’t want that—I wanted a warm, sunny painting of a dark-skinned woman.” A female subject’s sense of comfort, she added, is its own assertion of power.

A different kind of feminine potency infuses Chloë Saï Breil-Dupont’s Horn of Plenty, Portrait de Laura: In the foreground, the artist has painted fleshy, carnivorous venus fly traps. The female subject holds a series of rectangular “cassettes,” or freeze frames from paintings, events, or films—David Lynch, Dario Argento, and Federico Fellini have been major influences on the artist. One cassette depicts a female bust, while others display a pair of lips and shattered glass; eerie, cinematic glamour pervades the scene. Breil-Dupont gestures at, and undermines, the male artists and directors who have examined women with their own objectifying or violent gaze. Lukas Luzius Leichtle is similarly interested in imbuing his figuration with a sense of theatricality. A curtain conceals the top half of one of his subjects, while another subject suspends himself upside down, perhaps mid-performance, his arm blocking his head. While his figures appear vulnerable with their bared flesh, on their knees and inverted, Leichtle also offers them a sense of privacy and anonymity as he hides their faces from the viewer.

In the context of all this work, Christopher Hartmann’s paintings can seem like outliers. Two of his canvases feature a close-cropped, faceless figure putting on a tube sock. Hartmann narrows in on the crinkles of a bedsheet and his subject’s crotch, giving the scene significant erotic undertones. On two other canvases, the figure disappears completely as Hartmann focuses on just socks and boxers, with peach shapes around the edges that conjure but don’t clarify flesh itself. Here, Hartmann asserts an ambiguous relationship between subject and artist—seductive and marked by notions of absence and presence.

Exhibited in an Antwerp-based gallery, all these artworks are, in their own ways, haunted by the ghosts of art history. Working out of the city in the 17th century, Peter Paul Rubens laid the groundwork for centuries of figurative art as he made studies of live models, then repurposed them for religious scenes. Two of the drawings in the show—Delacroix’s inky Massacre of the Innocents and Fragonard’s sketch, Nymphs surprised by satyrs, (1761) (both after Peter Paul Rubens), riff on Rubens’s work with a sense of both reverence and rebellion. A similar spirit pervades all the contemporary pieces in FLESH—the artists have variously studied and synthesized elements of odalisques, transcendental poetry, and Italian cinema as they’ve each developed their own unique aesthetic. It’s just one of the productive tensions that transcends the exhibition: how to look backward and forward at the same time, wring meaning and depth from surface appearances, transform skin into a vehicle for aesthetic experimentation and expression, and do it all with an ethical and progressive approach. These frictions are, ultimately, the flesh of figurative art itself.

Words by Alina Cohen